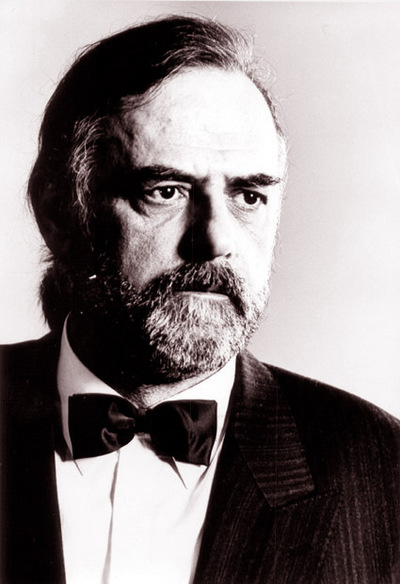

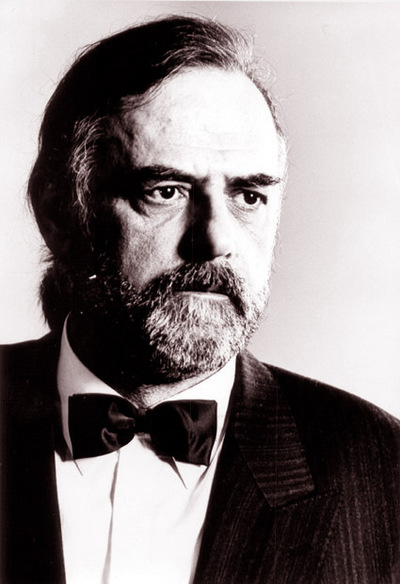

Rahmetli Nedžad Ibrišimović, 1940-2011

|

Nedžad Ibrišimović, a distinguished Bosnian Muslim sculptor and author, died in Sarajevo on September 15, at 71. He was a combat veteran of the 1992-1995 war that divided his country, and served as president of the Writers' Society of Bosnia-Hercegovina from 1993 until 2001.

Nedžad's name will have echoes among Mexicans thanks to the publication in 2000 of his novella, The Book of Adem Kahriman, Written by Nedžad Ibrišimović the Bosnian [El libro de Adem Kahriman, Escrito por Nedžad Ibrišimović el Bosnio], by Breve Fondo Editorial, as translated into Spanish by Antonio Saborit and me.

When the book appeared in Spanish, it included a preface by Nedžad that surprised us, in which he recounted his visit to Mexico in 1982. Bosnia-Hercegovina then, two years before the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics, was a constituent "republic" of Yugoslavia, a country that notwithstanding its Leninist legacy granted its citizens passports to travel abroad. As Nedžad wrote, "I did not like to travel, but when I was asked if I wanted to go somewhere, I said I would like to see Mexico." He had previously visited Paris, staying only ten days, and had returned from there disappointed.

Mexico, however, left him delighted, as it has so many foreign writers and artists. Indeed, The Book of Adem Kahriman, written a decade afterward, included praise of the brothers Zapata, Emiliano and Eufemio. Nedžad requested an interview with Juan Rulfo, whose works he admired, but who was, he heard, reserved, and reluctant to accept visitors. He obtained an encounter with the Mexican author by declaring that he had travelled 5,000 kilometers to see him, and was granted a meeting on February 2, 1982 – the date deserves to be specified because as Nedžad himself said, he remembered every detail of it eighteen years later, although he had never written anything about it.

Nedžad had described, as the reason for his visit, "to study the bright and dark aspects of the Mexican Revolution. I said that I went there to meet the autor of Pedro Páramo." Writing in retrospect, Nedžad admitted to motives common to many visitors before and after him: he was seduced since childhood by the "soft sonority" of Mexican trumpet music, but did not say so out of fear he would be told that in Bosnia he had already heard the Mexican trumpet and had no need to travel so far to listen to it played. Affection for the Mexican trumpet style, a common trope among tourists in Mexico, went along with his first act on reaching the country: he put on a sombrero and did not remove it until he returned to his home.

Rulfo, meeting this exotic visitor in his sombrero, commented, perhaps sardonically, "Yes, it's hot!" The two writers discussed their works, and Nedžad asked Rulfo for a list of books to read on the Mexican Revolution. Rulfo provided him with 12 titles by 10 authors, which Nedžad did not reproduce, though he described the scrap of paper on which it was inscribed as one of his most valued possessions. To a Bosnian, who had lost much, and whose life was endangered on the front lines of the Bosnian war, this latter comment said much about Nedžad and his personality. Coming from a land where the Partisan-revolutionary tradition that emerged from the second world war was still vivid in collective memory, Nedžad commented to Rulfo "there are those who have argued that in Mexico the revolution is still going on." But Rulfo replied, "The rifle fire is not heard!"

Interrogating himself on why Rulfo was so important to him, Nedžad cited the influence ofPedro Páramo, and added his admiration for Rulfo's comment, "To write… I never though that thirty years after the product of my obsessions would be read in Turkish, Greek, Chinese, and Ukrainian. It isn't because of my merit. When I wrote Pedro Páramo I only thought of how to free myself from such anguish. Because writing makes you suffer seriously."

Nedžad then added, in his preface, that when he wrote The Book of Adem Kahriman he hoped it would be read in the rest of Europe. It did not occur to him that the first foreign edition would appear in Mexico. Earlier in his preface, Nedžad had noted, "I called out to the translators who were listening to me and who had translated previously some of my works in the Czech Republic, Turkey, Albania, Italy, France, England, Germany, to turn on their tape recorders, to transcribe and translate the story of Adem Kahriman… The request was not fulfilled." Regular communications by telephone and mail had been cut off, and he had hoped foreigners would take notice of readings from the book that he gave over a small radio station in the Sarajevo suburb where he defended his community with arms in hand. But that expectation was unrealistic. For that and other reasons, a foreign version was delayed more than eight years.

The Mexican edition, on the cover of which the publisher ironically placed a detail from an unattributed painting of "Victories of Emperor Carlos V: Raising of the siege of Vienna, 1529," enjoyed a "succès d'estime" in Mexico, given its short press run. In his column "Escalera al cielo" in Reforma of January 7, 2001, Sergio González Rodríguez listed El libro de Adem Kahriman as one of the best books published in Mexico in 2000.

The death of Nedžad Ibrišimović recalls to me my own discovery of his book and the path that led to its publication in Spanish. On a rainy day in Sarajevo in 1997, while visiting the country after the war, as a representative of the International Federation of Journalists, I passed by the very elegant 15th century Imperial Mosque on the southern bank of the Miljacka river, which flows through the city. I took shelter from the downpour in a small kiosk nearby, where an old man sat with a stove, a pot and cups for preparation of Bosnian coffee, and piles of books on Islamic topics. I was offered and accepted a coffee, and then another – since in the Balkans a single coffee is "enemy coffee" (dušmanska kahva), because only one coffee is an expression of politeness rather than an invitation to friendship.

I knew little of the Bosnian language then, and asked after works in English. The old man in the kiosk – both of which have disappeared in recent years – handed me The Book of Adem Kahriman, Written by Nedžad Ibrišimović the Bosnian, in a bilingual edition of the kind where the back cover, beginning the translation, reverses the front. The book was issued in 1994 – during the war – by a Bosnian Muslim patriotic and Islamic house, Ljiljan, along with the state publisher Svjetlost, in a translation by Zulejha Ridjanović. To be charitable, the translation was faulty, but given the aforementioned difficulties of publication in wartime, that could be forgiven – although Antonio Saborit and I later had to work assiduously to correct some mistaken renditions from Bosnian into English, before producing its Spanish edition. But Antonio's verve and sophistication as a translator made the task easier.

Although it comprised only 100 pages in bilingual form, The Book of Adem Kahrimanimpressed me immediately as the simplest and most eloquent presentation available of the tragedy that had befallen the Bosnians at the hands of the their Serbian neighbors. The Book of Adem Kahriman is not a painless, clever, or folkloric book. It has its seemingly magical elements, which have to do with the resistance in which Nedžad participated, in the Serbian siege of Dobrinja, a suburb of Sarajevo next to the city's international airport, and part of which was awarded to the so-called "Republika Srpska" or "Serbian Republic" by the Dayton Accords of 1995. Dayton ended fighting in the country but left it divided, effectively rewarding the Serbian aggressors for their actions. The protagonist, Adem Kahriman, is married to a Serb woman, Ljeposava Jović, who has chosen to remain with him and defines herself as "Yugoslav" rather than as Serbian. Kahriman, a sculptor, is writing a book that will, by its existence, somehow prevent war crimes, even if they have taken place some time before, and he creates slender, Giacometti-like statues that Kahriman fears are offensive to the widely-accepted Muslim but non-Quranic ban on depiction of the human form, although he continues to produce them.

Adem Kahriman, as a literary character, is a Muslim believer and a free being who reads the verses of the 13th century Persian Sufis, Jalalad'din Rumi and Sa'adi Shirazi, as well as the mystical writings of the obscure, 10th century Brotherhood of Purity (Ikhwan as-Safa), and Bosnian literary and historical classics. The narrative navigates temporally between the second world war and the more recent Balkan conflict. Some of it retells brutalities that are difficult to face. But it presents the Bosnian Muslims in a human idiom that separates them from the stereotypes about Islam that were then common regarding the Bosnian war, and which have become commoner in the 10-year aftermath of the atrocities of 2001. I bought and handed around several copies of it, and when Antonio mentioned the possibility of its publication in Mexico, I was overjoyed.

The Mexican edition came out while I was living and working in the Balkans, and after I had met Nedžad Ibrišimović face to face, during the 1999 Sarajevo Poetry Days, an annual festival that began in 1961. Readings were held for a week, at the House of Writers, a club administered by the Society of Writers of which Nedžad was then still president, and typical of the former Communist world, but pleasant enough with its restaurant and patio, as well as in three high schools and at a downtown theatre. The events were varied, but serious and respectful, and drew crowds of young people along with their parents. The festival included verse written for children, and none of the affectations common in Anglo-American poetry events today – there were no screams of rage, even against the Serbs.

Indeed, when the recent war was alluded to, references were muted. As Nedžad entered the theatre I recognized him from a framed drawing in the House of Writers, where he was depicted in the uniform and beret of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina. He was erect and dignified, dressed for the reading in a somewhat formal, civilian manner. I was a member of a small delegation of foreign poets, and quoted two lines from The Book of Adem Kahriman when my turn came to read: "There are only seven words that can make me think clearly… Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina. When I say these seven words there is no question I cannot answer." And there began my intímate acquaintance with Nedžad.

Then our Mexican book appeared, and I bécame closer to Nedžad in later years, visiting him in the hospital during medical treatments he underwent in the period leading to his death. He was anxious for publication in English of one of his last books, Vjećnik, a novel issued in 2005, with an invented Bosnian word as its title, combining the sense of "passage" and "witness." He wanted it to appear in English as "Eternee," another invented word, and admitted that it was a difficult work for Bosnian readers, as it would likely be for foreigners. In 2010, the book was issued in English as Eternee, in Sarajevo, by the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia-Hercegovina, of which Nedžad was a corresponding member. His last book, published this year, was a sequel to Vjećnik, with the title Al-Hidrova Knjiga (The Book of Al-Khidr), referring to a mysterious spiritual companion of Moses, who appears in Qur'an but not in Jewish scripture. Both of Nedžad's volumes recount the experiences of a man who has lived thousands of years and seen the events of history from Egypt to Bosnia. While these themes are reminiscent of Sufism, Nedžad disclaimed any standing as a Sufi, declaring that he was merely an ordinary Muslim believer, who attended Friday mosque services.

Nedžad was born in Sarajevo in 1940 and completed academic studies in sculpture and philosophy. He later contributed to the student periodical Naši Dani (Our Days) and the dailyOslobodjenje (Liberation). Oslobodjenje was established by the antifascist Partisan movement and received due recognition during the 1992-95 war for the heroic efforts of its staff to continue publication under severe fire, including the destruction of its multistory tower, which had been a Sarajevo landmark. Nedžad worked as a teacher in the eastern Bosnian town of Goražde, but committed himself to writing as a profession.

With the commencement of the Serbian attack on Bosnia-Hercegovina he immediately joined the defense of the country as a soldier in the Third Company of the First Dobrinja Battalion of his country's forces. He later said that the other fighters at the front had been glad to provide him with a work space as a writer and the use of their radio to broadcast his work-in-progress. He had not been prominent as a Bosniak nationalist, and later confessed that he did not understand what was happening, even when the war began in 1992, until he saw a soldier with a rifle from a window of the building where he lived.

Toward the end of his life he restricted his public activities to encounters with children in the primary schools, protesting that he lacked time for seminars, conferences, and other major literary events. He said he had "always felt uncomfortable, as a writer, in public life," although he served as a regional councillor from the dominant moderate-Muslim Party of Democratic Action (Stranka Demokratske Akcije or SDA).

His early, more conventional novels deal with Bosnian Muslim culture in its own environment, and he expressed distaste, before his death, for the success other Muslim writers had gained in Europe and elsewhere by attacking their native lands and their religion. His first novelUgursuz (The Ruffian) received a literary prize from the city of Sarajevo in 1969, and is set in Bosnia during the political upheavals of the 19th century, when Ottoman reforms and Austrian ambitions alike brought turmoil to a traditional society. His next two novels, which continued this theme, were the 1970 Karabeg, and the 1989 Braća i veziri (Brothers and Viziers). Nedžad also produced volumes of short stories, theatre, poetry, and essays.

I have called him by his first name throughout this recollection because I appreciated his friendship and considered him a teacher and mentor on my life's path. I know that his modesty would have led him to reject all such praise as excessive. He was satisfied to be who he was: a chronicler of his country and its religion, a defender against its enemies, and, above all, to repeat, an ordinary Muslim believer. But I know he was loved by the people of Sarajevo, as I love them and as I admired him. He represented the dignity of Bosnia, its culture, and its history, neither more nor less.

[CIP Note: The original Spanish-language text of this article may be accessed by placing your cursor on the title Reforma at the head of the entry.]