Being unconvinced by its central thesis, it's only fair to begin by signalling the better side of this Kadarography. Peter Morgan's opening survey of Albanian history from ancient to modern is exemplary in its breadth, depth, and punctilious detail. And, throughout, his literary analyses (up to a point, see below) are the most thorough-going yet attempted in English, from which the reader, Albanologist or general, will learn a lot, as did I.

To my taste, though, Morgan goes overboard in detecting discreet anti-communist sentiments in the smallest of details, a good/bad example being the three pages (133-35) on the supposed multi-symbolism of spectacles in Chronicle in Stone, leading to such bafflegab as: 'If the glasses of the intellectuals give access to the worlds of modernity, the black eye sockets of Kadare's blind seers are the means of access to the underworld of Albanian reality.' To what extent these expiscations are Morgan's own, or provided/invented by Kadare, with whom he is on close terms, is hard to say. For contrast, see Savkar Altinel's review (TLS December 7, 1990), dismissing Chronicle in Stone as 'by and large conventional, without being especially adventurous or innovative,' also tracing an unacknowledged debt to Yugoslave film director Ernir Kusturica's When Father Was Away On Business.

For example, Alan Brownjohn (TLS September 5, 2003), observes that Derek Coltman, who in 1971 Englished Albin Michel's French version, added to his republication 'numerous authorial revisions incorporated in the 1998 French version.' As I have frequenty mentioned in print, in the analogous case of another spurious dissident, Kadare's protégé Neshat Tozaj, his novel Të Thikat (The Knives) was on authorial admission doctored in some sensitive political areas.

Morgan (283-293) is in thrall to Kadare's ultra-patriotic and largely baseless attempt in his Aeschylus, or The Great Loser, to transfer credit from Greece to Albania for the origins of folklore tales concomitant with tragic drama, with the silly conclusion that Aeschylus was the 'great loser' because only seven of his ninety plays have survived. Exactly the same fate befell Sophocles, on this reckoning an equal loser. More to the present point, Robert Elsie, the greatest living authority on Albanian literature and overall admirer of Kadare's work, appends to his review of the Aeschylus (repr. in Studies in Modern Albanian Literature and Culture, 1996, 67-68) examples of how Kadare fiddled with the text of Cavafy's Greek poetry in his 'translations' thereof, respectively adding and subtracting verses to change the meaning. Elsie cannot decide if this is Kadare the nationalist or Kadare under political pressure at work.

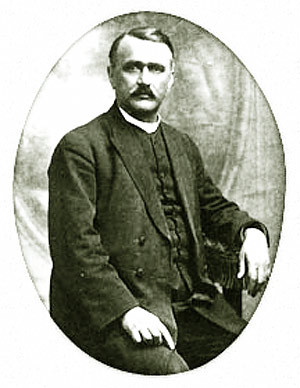

Fr. Bernardin Palaj, O.F.M. (1894-1946), outstanding folklore collector with his colleague Donat Kurti. Palaj was executed by Hoxha's thugs. Ismail Kadare "borrowed" the works of Palaj and Kurti while grossly insulting them.

|

|||||

Likewise, with the anti-Kadare polemics (online) of Janice Rrapi and son Renato, who maintain that Kadare used his influence to have Renato arrested and confined to a mental hospital in order to break up his romance with Kadare's daughter. Family feuds have been endemic to Albania for centuries. Kadare may hint at his own indulgence in suchlike through his absurd laudatory contrasting in the novel Broken April that regulates the traditional murderous vendettas with communism, an attitude in which Morgan tamely acquiesces. It was actually to the credit of the communists that they tried to eliminate these. A vain effort. They remain rampant: an article in the magazine MAPO (June 10, 2010, alluding to a BBC television doumentary of this same year conducted by Philip Alston) estimates that in 2009 at least 90 people were killed in these family feuds, with 1450 (including 800 children) currently immured in the traditional towers of refuge. How can any reasonable person approve this way of life and death?

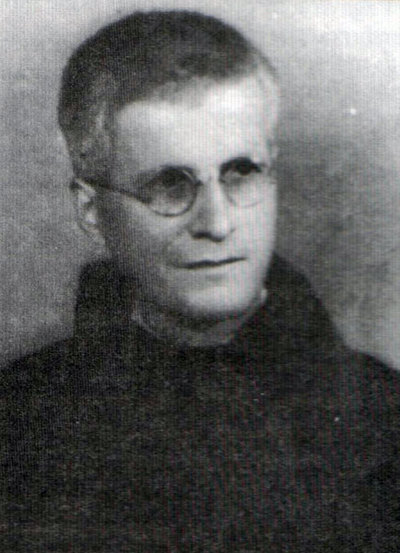

Fr. Donat Kurti, O.F.M. (1902-83), imprisoned from 1946 to 1963 under Hoxha's misrule.

|

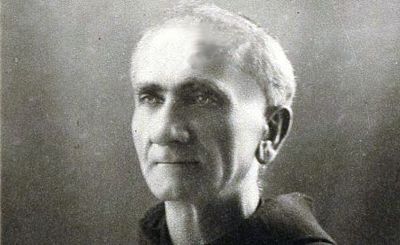

Dom Ndoc Nikaj, S.J. (1865-1951), pioneer of modern Albanian publishing, executed by order of Hoxha, viciously defamed by Ismail Kadare.

|

I also add, as Morgan (228) does not, that two of Kadare's novels, General of the Dead Army and Broken April, despite the supposed bad reception of the former and anti-communist elements in both, were filmed by the state-run AlbStudio, another surprising honour for our suspect dissident.

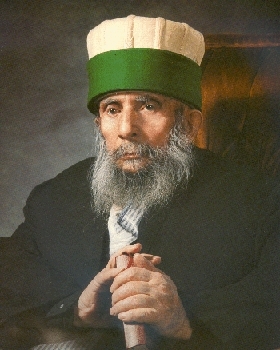

Rahmetli Baba Rexheb Beqiri (1901-95), exiled because of his anti-Communist patriotism, founder of Albanian Bektashism in the U.S. and guardian of its traditions.Fatiha.

|

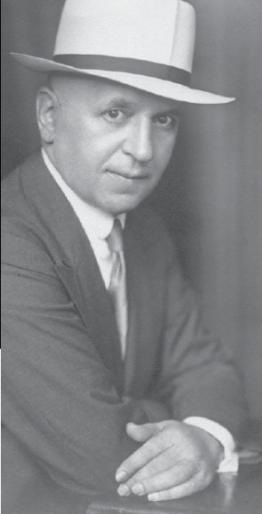

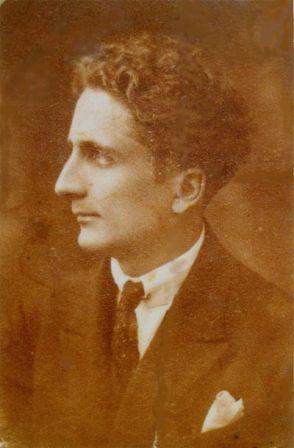

Llazër (Zai) Fundo (1899-1944), poet, comrade of Avni Rustemi (1895-1924), supporter of Imzot Theofan Stilian Noli (1882-1965), anti-Stalinist revolutionary. Brutally murdered by Hoxha's killers in Albania.

|

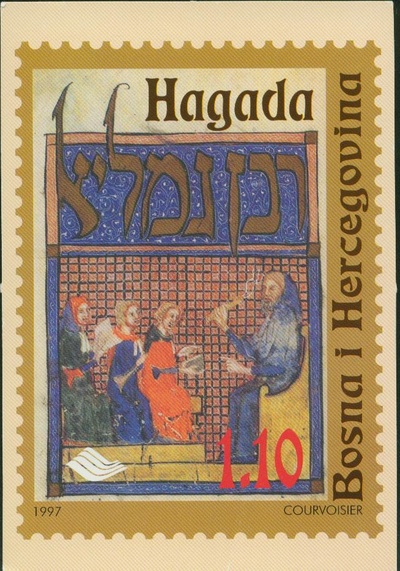

Postage stamp issued by the Republic of Bosnia-Hercegovina honoring theSarajevo Haggadah. Ismail Kadare denounced the Jewish Torah, the Gospels and Qur'an with equal vulgarity, See bold citations in paragraph 8 above.

|