Erdoğan's Meddling in the Balkans

.

The Blue Mosque, Istanbul, 2007 -- Photograph Via Wikimedia Commons.

|

The soft-Islamist Turkish government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development party (known by its Turkish initials as the AKP) has expansive foreign-policy ambitions. In addition to its

embrace of the Hamas regime in Gaza and accompanying criticism of Israel, Ankara has

sent naval and air units into the eastern Mediterranean in a bid to intimidate Cyprus from exploiting, with U.S. economic

partners, the divided island's offshore energy assets. Turkish military maneuvers near Cyprus parallel threats of a similar seaborne campaign to shield another Gaza flotilla operation against Israel's maritime security patrols. Turkey has acted

ambiguously toward the NATO missile-defense system intended for protection from Russian or Iranian attack, after

indicatingcooperation with the plan developed by the Western alliance.

In more benign-appearing efforts, Turkey has switched from supporting the bloody dictatorship of Bashar Al-Assad in Syria to

declaring an arms embargo against Damascus, and has sought a leading

role in aid to post-Qaddafi Libya. But a key aspect of AKP's efforts at a "neo-Ottoman" revival of national prestige is typically neglected by Western observers. That is, Erdoğan has sojourned repeatedly as a triumphant patron in the former Balkan provinces of the Turkish empire, including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and, most recently, Macedonia. All these countries were ruled from Constantinople until the last quarter of the 19th century, in the Bosnian case, and the first decades of the 20th, in Kosovo and Macedonia.

At the end of September, Erdoğan travelled for two days to Macedonia, which has a Turkish-speaking minority of at least 80,000 people, or up to 4 percent of its population of two million. Turkey has

raised its investment profile significantly in Macedonia as well as the other Balkan states, in competition with Russia, which views them as part of its post-Communist Slav sphere of influence. The Macedonian government

claims Turkey's support in the long-festering quarrel with Greece—Turkey's main international rival—over the very name "Macedonia," which Athens asserts may only be applied to its own northern territory.

The AKP offensive in the Balkans is cultural as well as economic and geopolitical, involving Turkish government subsidies for new local high schools and universities. Further, Turkish officials call for the Balkan Muslim-majority nations to revise how they teach the history of Ottoman dominance over them. In Kosovo, Turkish education minister Omer Dinçer, during a mid-August visit, asked for removal of material from schoolbooks that treated negatively more than 500 years of Turkish rule in the Albanian lands, from the 14th to the 20th centuries. AKP foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu likewise

complained during a Kosovo tour two weeks later that Turkish power was portrayed critically in local textbooks.

Lekë Dukagjini Primary School, Prizren, Kosova, 2010, named for a notable anti-Ottoman Albanian patriot -- Photograph Via Wikimedia Commons.

|

The Kosovo government's education minister, Ramë Buja, has been occupied with

defendingsecular education in the republic against Islamist pressure. But he promised the Turks that new educational materials would appear next year, based on the work of a research commission that went to Turkey. Kosovar Albanians, especially members of the small but vocal Catholic community, have expressed unease over the rewriting of school texts. A Catholic Kosovar, Ndue Ukaj,

commented to the regional

Southeast European Times, "Turkey must show greater tolerance toward Albanians, to accept the historical facts and repent for the destruction of numerous invasions. . . . The period of Ottoman history is what it is."

The majority of Albanians accepted Islam as a faith during the Ottoman period, but were never reconciled with foreign supremacy. They began asserting their desire for national independence in the 19th century. That struggle, which turned into war against the Turks, was led by Albanian Muslims as well as Christians.

In addition, the late-period Ottomans and their successors under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk dealt abusively with the spiritual Sufi orders. The Sufis attracted considerable adherents among Albanians, and their suffering at Turkish hands has not been forgotten. When the Sufis were officially suppressed in Turkey after World War I, the powerful Bektashi order moved its headquarters to Albania, and became Albanized in its culture. Albanian Bektashis, who are dedicated to secular governance, female equality, and mass education, may account for as many as a quarter of all Albanians in the world, or at least three million people.

Since 2002, one of the most important Sufi monuments in Europe, the Harabati Baba Bektashi shrine complex in Tetova, a city in Western Macedonia, has been under siege by Arab-financed Wahhabi radicals. Tetova has an Albanian majority alongside Turkish-speaking and Slavic residents. The extensive

attacks on the Harabati Baba Bektashis have been

noted by the State Department and culminated in an arson attempt last December. But the rest of the world has paid little attention to a confrontation in such a little-known place.

Arson damage at the Harabati Baba Bektashi Shrine, 2010 -- Photograph by the Bektashi Community of the Republic of Macedonia.

|

During his recent visit to Macedonia, however, Erdoğan made a point of going to Tetova and offering Muslim prayers at the Harabati Baba shrine. According to Bektashi Sufi leader Baba Edmond Brahimaj, interviewed by Albanian-American media, Erdogan's appearance was preceded by more Wahhabi vandalism at the site.

The Harabati Baba shrine, although once an Ottoman institution, is not a mosque, although the Wahhabis who have occupied it claim to have installed one there. Bektashi devotions do not include regular Muslim prayer, even though, paradoxically, the Bektashi order was long a pillar of the Ottoman state. A Sufi who remains at the diminishing property to care for it, Dervish Abdylmytalip Beqiri, remonstrated with Erdoğan and his group, pointing out that there was no mosque at the site where they could pray. Tetova includes numerous Sunni mosques, mostly from the Ottoman period, and some of them are distinguished architecturally.

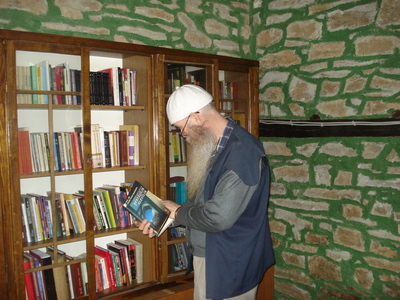

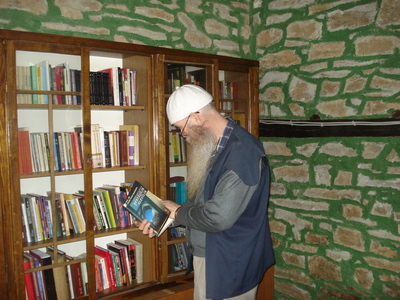

Dervish Abdylmytalip at Harabati Bektashi teqe, 2010 -- Photograph by the Bektashi Community of the Republic of Macedonia.

|

So Erdoğan prayed in the meydan, or open square in the middle of the Harabati Baba shrine, surrounded by buildings usurped and damaged by fundamentalist fanatics. To the Bektashis, Catholics, and other Albanians critical of the Turkish historical legacy, visits by Erdogan and his ministers, in which they advocate editing of textbooks and appear to approve of the destruction of symbols of heterodox identity, embody the same cultural devastation that Albanians, Muslim as well as Christian, equate with the Turkish onslaught of the past.

Municipal shield of Tetova, Macedonia, showing the Harabati Baba Bektashi Shrine

|